Origins

The idea for Animal Rescue Team began in a conversation with my family as we walked our family dog, Fintan around the block (1). We were brainstorming different possibilities for rescue games because the license for one of my games had run out and I had the opportunity to revisit it.

Unless you were really into 1960s-era kids’ shows featuring marionettes, you may have missed that game. It was called Thunderbirds. In the game, players go on rescue missions around the globe. You have to gather the right rescuers, vehicles, and equipment in order to have the best chance of success. The game requires you to make constant tradeoffs between risk and efficiency, has a lot of tension and storytelling elements, and did quite well when it came out in 2015.

We discussed what players might rescue in a new game with a rescue theme and remembered the game Animal Rescue that my daughter had prototyped when she was in elementary school (2). What if the players were rescuing animals? While discussing it, we quickly realized that we knew a real-life animal rescuer – our friend, Lisa Towell! I contacted her shortly after our walk and was delighted to hear that she was up for helping to design the new game.

Lisa and I started out by building out some tables for translating the game’s characters, rescues, vehicles, and setting over to the new theme. I looked at things through a mechanical lens (how might the game’s mechanisms change to fit the new theme?) while Lisa looked at the design from the other direction (how might the game’s new theme change the existing mechanisms?). During our early conversations it became apparent that we had two main goals. We wanted to center the game on animals and we wanted to improve on the previous game wherever we could.

Goal 1: Spotlight the Animals

One of our early ideas was to embody the animals you were rescuing in the game, making them an important part of play. Perhaps in the new game, you could actually see the animals and load them into your vehicle when you completed a rescue. This not only fit the game’s story well but it leaned into one of the elements of Thunderbirds that people reported enjoying the most. In that game, you could load “pod vehicles” into Thunderbird 2, fly them around, and drop them off in order to complete rescues. In this new game, we could give players the option to load and unload animals and equipment into and out of every vehicle.

We also wanted to be respectful of the animals shown in the game. We favored showing the animals in a naturalistic way (no exaggerated, Disney-like treatments to their eyes, faces, or proportions), give each of them their own names, and treat them – even the chickens and lab mice – as individuals worthy of being rescued. Lisa spent a lot of time directing the illustrators as well. She favored the depiction of animals of mixed breeds and wanted to make sure the little details were rendered appropriately. (Examples that I recall: “a goat’s tail points up!” and “OMG, you’d never hold a lead rope like that when handling a horse!”)

Like all of my games, we spent some time early in development on working out the language used in the game. Here’s an excerpt from one of our controlled vocabularies:

An excerpt from our long controlled vocabulary for the game

One dilemma: while we wanted the players to emotionally connect with the animals in the game, we didn’t want them to despair if they failed at a rescue or at the game. We used some strategies to provide some emotional distance for more sensitive players:

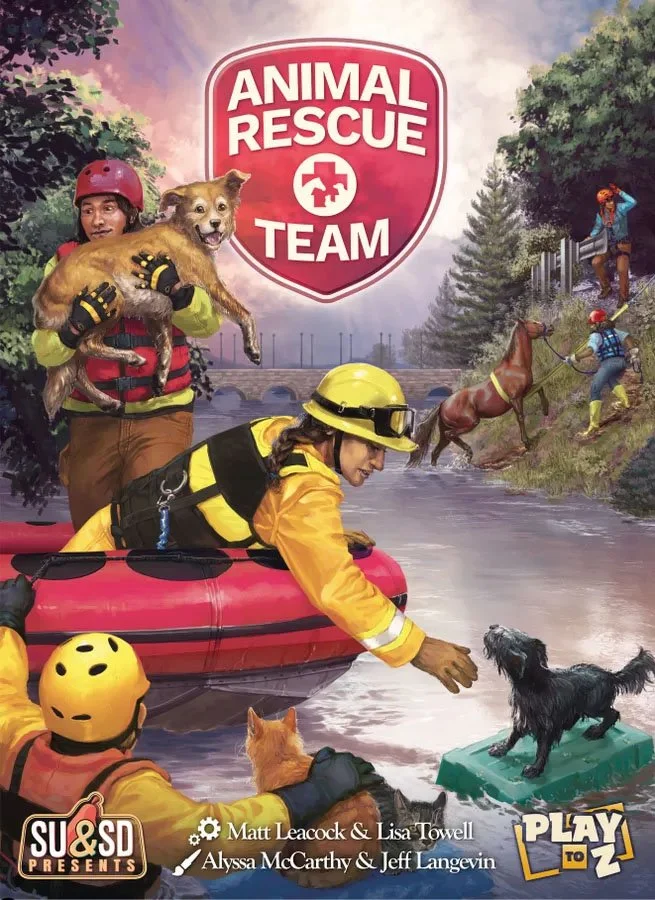

The cover of the game shows the animals in the act of being rescued – not in peril.

The illustrations on the rescue cards show the animals, but they’re never shown in danger.

While the short stories on each rescue card describe real-world rescue situations, that text doesn’t need to be read to play the game.

If you lose the game due to a failed rescue, we assure you that another volunteer rescue team comes to help. (And we suggest you buy them lunch as a thank you.)

We felt this approach maintained the game’s realism and tension while reducing the likelihood of upsetting players, especially young folks.

Goal 2: Lean into the Fun, Clean up the Janky

This was also a great opportunity for me to revisit the underlying Thunderbirds design and tune it up. My goal was to lean into the elements that worked well while cutting out the bits that were confusing, awkward, or unnecessary. Over the course of development, we made the vehicles more fun, improved the way the cards worked, dropped one type of action, modified the dice, and made a few other miscellaneous improvements.

Make the Vehicles Even More Fun

Animal Rescue Team makes use of six different vehicles and we really explored how they could be different and playful. They have a toy-like quality and we worked to ensure each vehicle’s form helped communicate its function.

A rabbit and a specialist on a motorcycle, on a truck

(prototype made from 3D printed resin and laser cut illustration board)

The speeds of each vehicle are printed directly on them, making it really clear how fast they can go.

Each vehicle can carry specialists, animals, and equipment and those pieces each take on a different form. Specialists are represented by pawns, animals are represented by animal meeples, and equipment is represented by tokens. You always know what you’re allowed to carry. If it fits, it sits!

We added a (non-drivable) trailer to fit large animals (horses, cows, and a tiger) (3). That led to the idea of towing vehicles. You can attach the trailer to the SUV or truck using a hitch that’s similar to the hook-up used in Brio trains.

We added a boat to the game for water rescues. This, in turn, led us to change the board’s topology. Players can move the boat between regions, provided they share a coastline, or they can hitch up the boat (like the trailer) and drive it between land regions.

We added a speedy motorcycle to the game which can be loaded onto the back of the truck, which essentially lets one specialist move two vehicles at the same time.

All these additions resulted in a lot of playful variety without much additional complexity. You can look at a vehicle and see what it can carry, how fast it moves, and whether it can hitch or be hitched to another vehicle or not.

Because the vehicles are also limited in what they can carry, they will start to fill up as they pick up animals. To solve this, vehicles can drop animals off at shelters (where they'll be cared for) in order to free up space — but the shelters also periodically fill up, leading to even more logistics problems.

Make the Special Cards Work Better

The game uses logistics cards which give players special one-time powers (these were called F.A.B. cards in Thunderbirds) and event cards which challenge the players with new circumstances or restrictions. Lisa brainstormed all sorts of different benefits and challenges that we could throw at the players and then we both set out to figure out how they might play out in the game.

Then, I made the following changes to the two systems so they would function even better in the new game:

I changed the event cards so players encounter an ever-increasing number of them at a time, escalating the danger as the game unfolds. In Thunderbirds, you only ever turn over one of these at a time, which often led to dead beats when a card didn’t really do much. I also added events that change the topology of the board by closing bridges or roads.

I addressed a problem I had with the F.A.B. cards in Thunderbirds. They always felt a bit random since they’re drawn blindly from the top of the deck. Now, in Animal Rescue Team, you can choose between two faceup logistics cards (essentially drafting them) or you can draw blindly from the deck in times of desperation. This gives the players more agency – they can purchase a card knowing it’ll help them. These faceup cards also now cycle as time progresses which lets you see the majority of the deck each game, instead of a limited handful.

To add more variety from game to game, we added more of each type to the game. There are now 18 event cards (up from 12) and 24 logistics cards (up from 18).

Other Tuneups

People who are familiar with Thunderbirds may be interested in the following other changes that we made between the two games:

I dropped the somewhat awkward “Plan” action that let you exchange an action for a random F.A.B. card since it was rarely used in practice. There are now only two possible actions in Animal Rescue Team: Move or Rescue.

I flattened the curve on the rescue dice. Thunderbirds uses dice that each show 0–5; Animal Rescue Team’s dice each show 0, 1, 2, 2, 3, 4 for a range of 0–8 instead of 0–12 when the two dice are summed together. It’s a subtle change but it means that each bonus matters more in proportion to the numbers that are randomly generated. (4)

Some rescues now escalate in difficulty the longer you put them off.

After a bunch of testing, I changed the rules so the eight “Time Ticks Down” cards are simply shuffled directly into the rescue deck during setup. Thunderbirds used a more complex setup (similar to Pandemic) where the deck had to first be split into smaller piles with these cards shuffled into each pile. This method eliminated the possibility that your game is derailed by a really bad shuffle. But those games are exceedingly rare and the special setup is complex and time consuming. This change also had the side benefit of raising the tension in the game since you can never know what you’re going to draw next.

Development Process

As we developed the game we did many rounds of playtesting with families, animal lovers, hobby gamers, cooperative game lovers, and lots of folks from the animal rescue community. We lent copies to friends, tested at conventions, and did video-recorded remote tests. The game changed in several ways over the course of development.

Animal Evolution

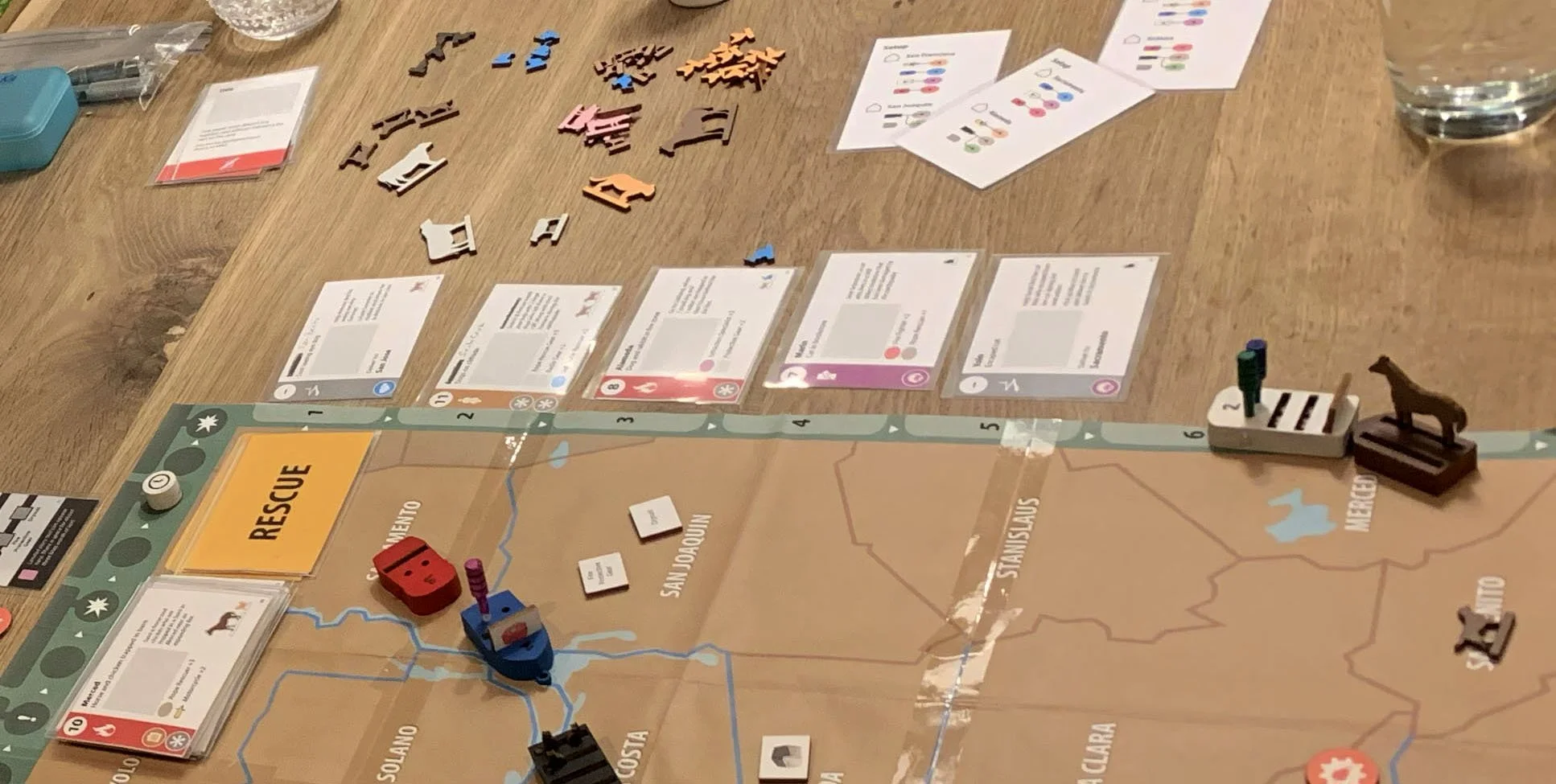

Of all the components in the game, the ones that saw the most iteration were the animals themselves. We started by representing the animals as simple wooden cubes, then punchboard tokens, then experimented with 3D sculpted miniatures, before finally deciding that wooden animal meeples were the best approach.

The first vehicles, specialists, and animals that I put together to show Lisa. Look at the two chickens, a dog, and a horse! It’s also clear at this point that I had no idea what sorts of vehicles would be used to rescue animals. (Take note: people do not typically pack dogs into a container pulled by a semi truck.)

The punchboard version of the animal tokens. When they were in the vehicles, they looked great. But they didn’t look so good when lying on the board. This photo also shows some color-coding on the vehicles that we later dropped.

Stock wooden pawns as specialists with sculpted, plastic animals (hand-painted 3D resin prints)

A prototype showing specialists, animal meeples, and shelters (all meant to be in wood) (5). We’re still developing the vehicles and equipment at this point. The equipment shown here is a simulation of screen-printed wood; we changed these to be punch board tokens in the final game since those felt better.

The first animals were simple wooden cubes, glued together that we used for rapid testing.

Punchboard tokens were the least expensive. We could fully illustrate these but they didn't have a very good table presence as you’d have to lay them down on their side before they were rescued.

Miniatures looked great but they introduced more plastic into the game and would have been quite expensive, especially if each species was in a different color. It also would have increased the overall size of the vehicles, and therefore the board, and then possibly even the box, adding to the game’s cost.

Wooden animal meeples however, could stand up, could be in different colors without much additional expense, and each would still have a distinct shape. They also looked better next to the wooden pawns we had planned to use for the rescue specialists.

Specialist Evolution

The specialists started out as pegs that were inserted into the vehicles but we then switched them to be wooden pawns which felt much better. The pegs always needed to be in a vehicle or shelter (otherwise, they’d awkwardly lie down and roll around on the board). Once we made them pawns, we realized they could simply stand on their own, outside of a vehicle or shelter.

Uhh… hello? Can I get a ride?

When we let them stand by themselves on the board, we realized that there were some situations where it made sense to leave one behind in a region, for example to make room for an animal in a vehicle. We soon learned that this can lead to unfortunate (and often, very funny) situations where you have all the best intentions of picking up your team member before their turn, but circumstances change – or you forget – and they’re left stranded, looking for a ride.

Rescue Card Evolution

The illustrations, structure, and design of the rescue cards evolved along with the rest of the game.

These cards have a lot of information to convey and need to do so efficiently so they don’t slow down play. Each card needs to communicate the rescue’s difficulty, the bonuses you can apply, its location, the animals you’ll need to place on the board, the bonuses you’ll get if you’re successful, a title, the story behind the rescue, and an illustration of the animal being rescued.

A selection of rescue cards as they evolved through various prototypes

We determined early on that it wouldn’t make sense to illustrate each rescue situation on the rescue cards. We didn’t want to show animals in peril, and if we did, the animals would be quite small. Such illustrations would also require a tremendous amount of art direction and expense. So instead, we put a hero illustration of the animals to be rescued on each card. We also learned that illustrating each location helped give the regions an identity that helped players find them on the game board.

Sample rescue cards showing final artwork. The one on the right shows our new method for showing scaling difficulty.

Zev Shlasinger, who runs Play to Z, wondered if some of the rescues could get harder the longer you wait to complete them. The idea worked well. Should you complete the rescue with a tight deadline or should you do a different rescue (that’s less pressing) but will get harder the longer you wait? The hardest part for these was encoding them in a way that didn’t force the player to do a lot of arithmetic.

World Building

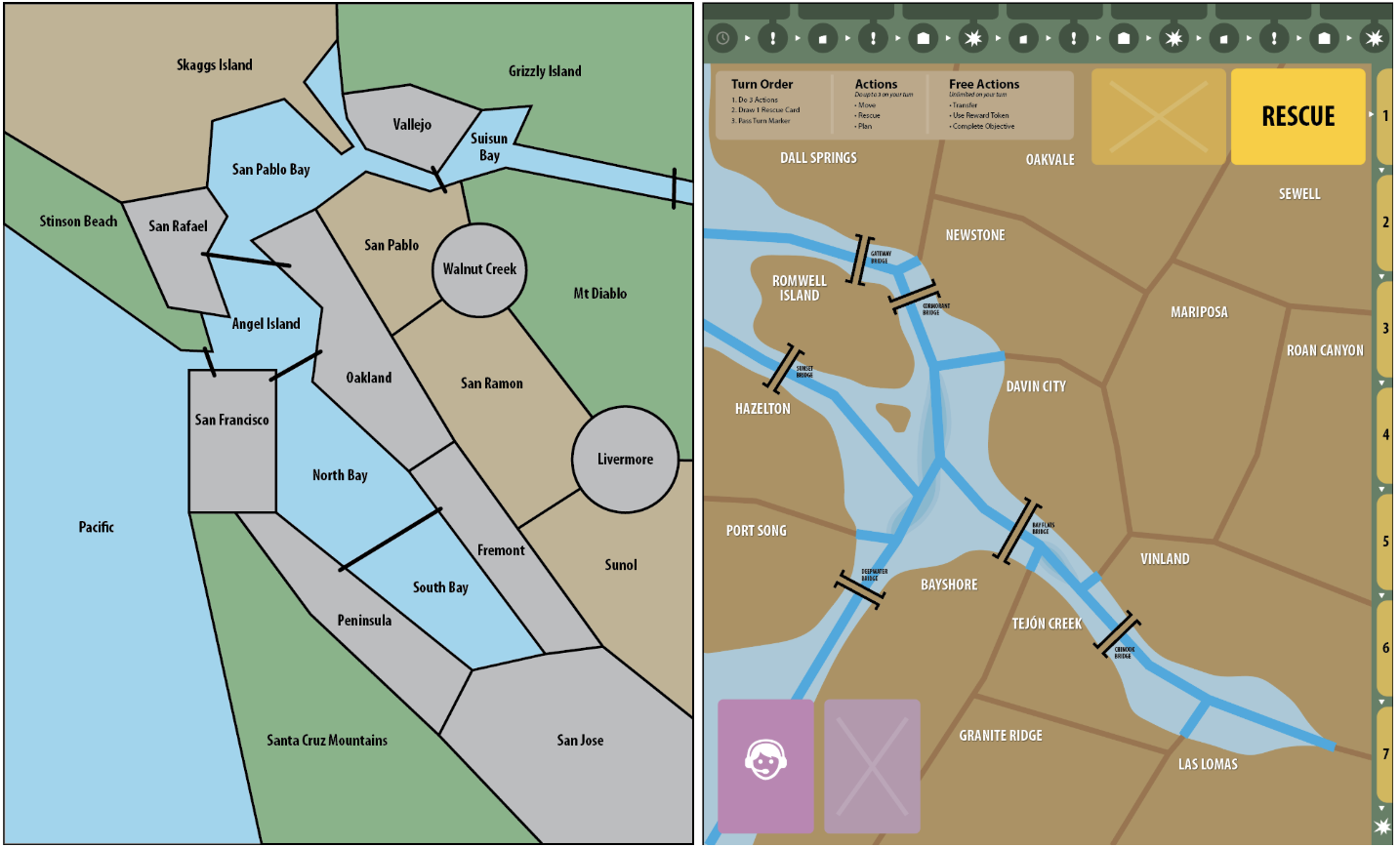

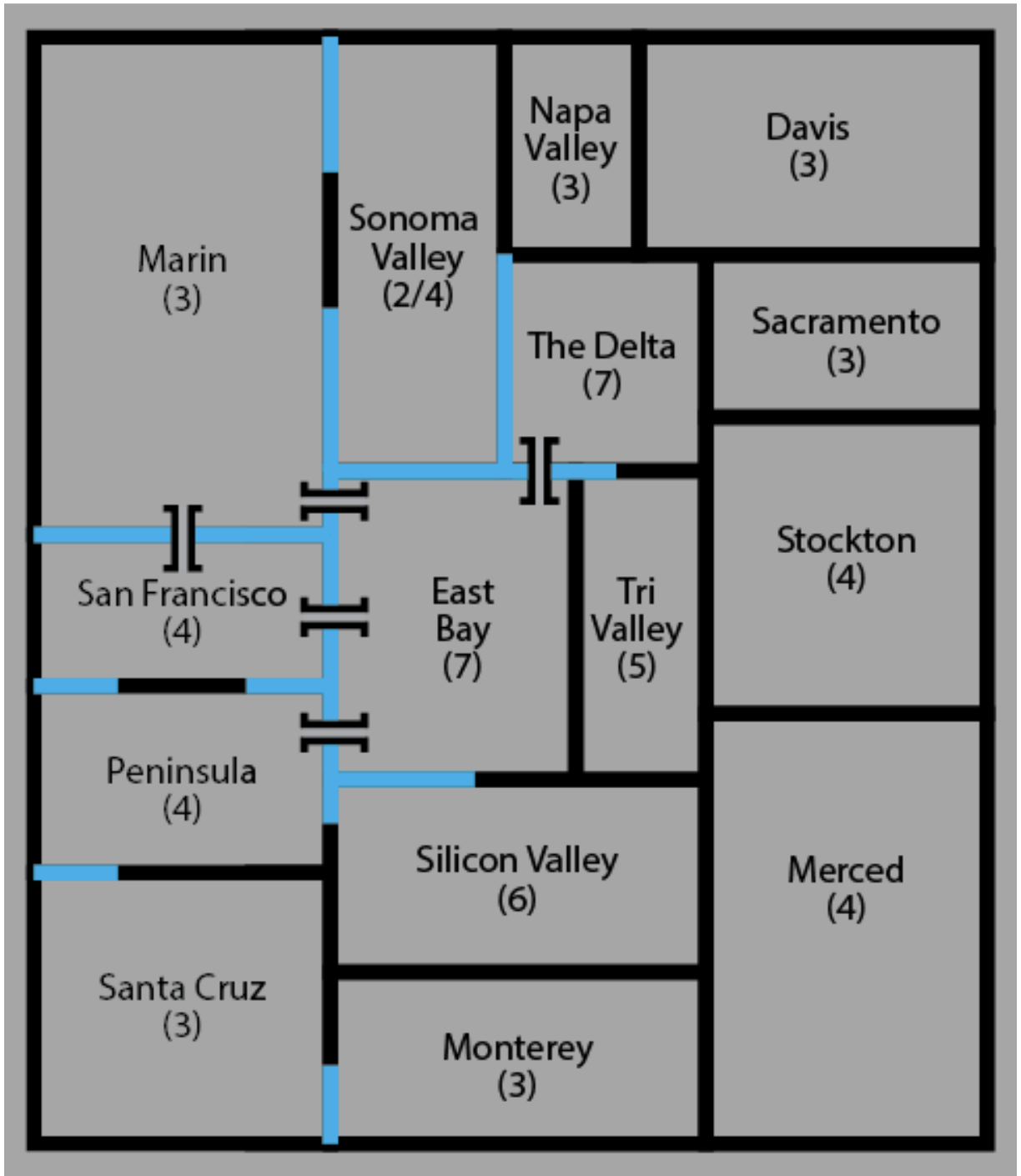

Lisa also spent a good deal of time building out the world in which the rescues take place. She started with something we both knew – the San Francisco Bay Area – but then we decided to change the setting to an imaginary world in order to give us more freedom with the design, and so the players could imagine this place being anywhere.

The first board (modeled after the San Francisco Bay Area) and the board during development. One key change was the integration of water into the regions so the boat could function as a rescue vehicle.

Another study of board topology. (If you ever need to get around in the Bay Area, print this out and take it with you.)

Lisa described each region in detail. These descriptions helped her write the different rescue stories and were a useful reference for the illustrator (Jeff Langevin) when he drew the board, rescue card, and mission card backgrounds. Since the game has come out, we’ve already been asked by several people if the game is set in a real place. I take that to mean it feels pretty authentic to folks.

Using her extensive experience in the field and from consultations with other experts, Lisa also supplied the majority of the details you see in the game. She wrote descriptions of the specialists, what they’d be wearing, the equipment they’d be using, the vehicles they’d be driving, as well as other notes on the logistics cards and event cards for the game. While the game isn’t a simulation, we wanted to take every opportunity we had to get things right.

A closeup of 3D printed proofs of the vehicles, animals, on an inkjet proof of the board

Results

We’ve been really happy with the outcome. Thanks to Zev Shlasinger of Play to Z, Tony Mastrangeli, and SU&SD for helping us really fine tune the product. Thanks also to the illustrators, Alyssa McCarthy, Jeff Langevin, Eric Hibbeler and the vehicle sculptor, Toan Nguyen. Special thanks to all the people in the animal rescue community who helped advise us on the game including Janice and Norm Rosene, for sharing their technical expertise; and Michelle Cehn, Lisa DeCarbo, Dan Miller, Rebecca Platt, and Claudia Sonder, for sharing their ideas. And thanks to our many playtesters.

We started this way back in 2019, before the lockdown, and even managed to steer the game from one publisher to another over the course of development. We’d also like to thank the folks at Z-man Games who helped Play to Z secure some of the wonderful artwork in the game. (Thanks Mike and Bree!)

How the Game Compares to Real Life (Lisa)

Working on this project with Matt has been fantastically fun for me – what a great opportunity to share stories about animal rescue with more people! Animal disaster response can be exciting, exhausting, surprising, heartwarming, and heartbreaking – but it’s always rewarding. I was thrilled to try and capture the whole experience in a board game. I hope that the game inspires people to create a disaster plan for their own animal companions, or maybe consider volunteering with their local animal disaster response team.

In our early discussions, we realized that we would have to take some creative license with real-life animal disaster response in order to suit the mechanics of the game, and to make the game more interesting and fun to play. Here are some of the ways real animal response compares to the game.

It’s More Than Just Field Operations

Real animal disaster response requires volunteers in many different roles. Hotline operators take calls from members of the public who need help with their animals. Field team members are assigned to visit properties to locate, assess, and transport animals. Shelter team members care for animals in temporary shelters until they can be reunited with their humans or transferred for adoption into new homes. Additional volunteers handle planning, tracking, logistics, radio communications, public communications, and other supporting roles.

We simplified things for the game by focusing just on the work of the field teams. In the real world, the field teams also do a lot of sheltering in place (in addition to evacuating the animals to shelters), but we decided that the addition of sheltering in place would be an unnecessary complication in the game.

Volunteer Animal Responders Can’t Do Everything (Even Though We Want To)

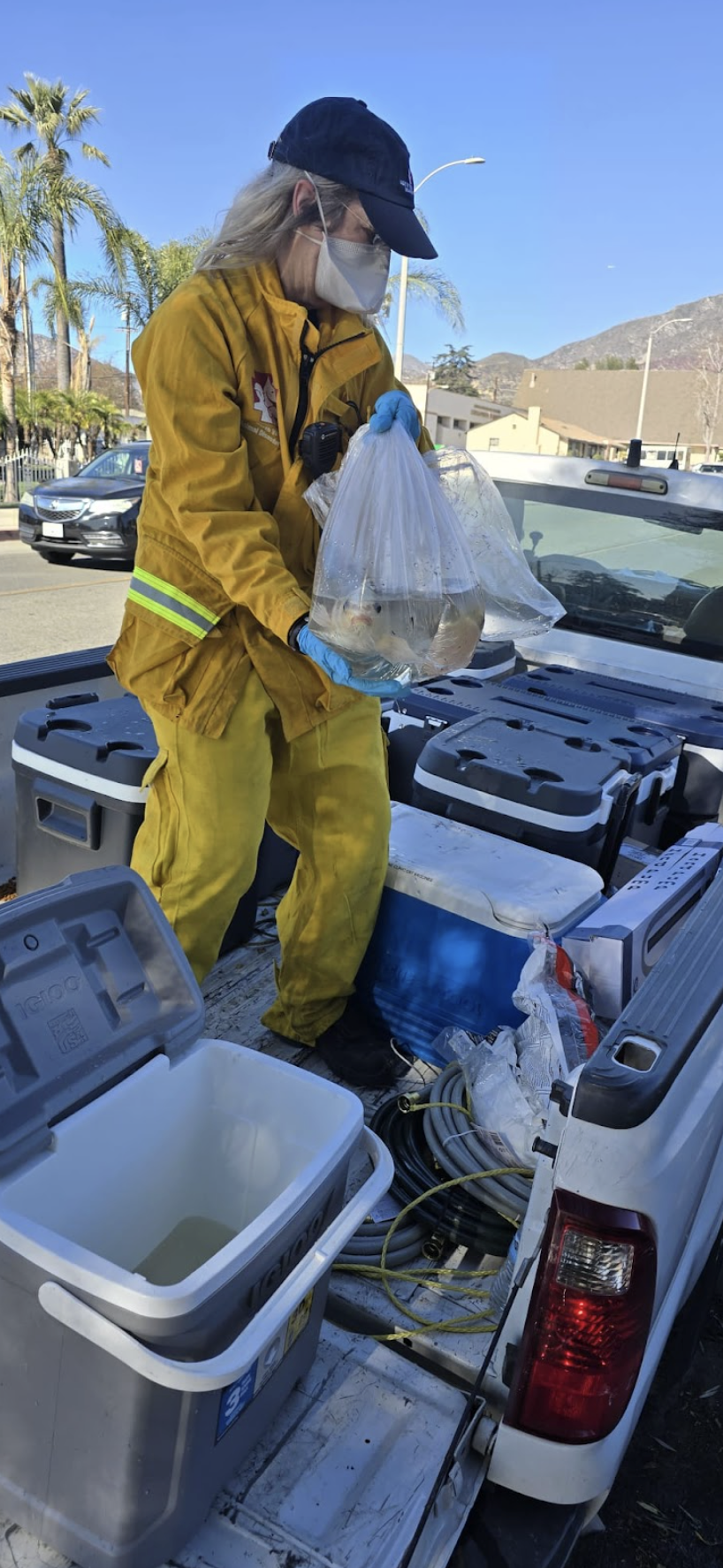

Lisa evacuating koi from a pond on a burned out property (photo courtesy of North Valley Animal Disaster Group)

The game's specialists (Firefighter, Swiftwater Technician, Extraction Specialist, Rope Rescuer, Veterinarian, and Animal Behaviorist) are real roles, but a typical team doesn't usually have so many skilled specialists on it. In the real world, we generally rely on trained professionals for the advanced stuff. We might request a team of veterinarians if any animals need medical care, or we might partner with local animal control officers who are experienced in handling aggressive and difficult animals. Animal response volunteers bring a wide range of skills and experience to the table – everything from species experts to SAR (Search and Rescue) volunteers to people who have never handled a large animal. Luckily, there are roles for everyone, no matter what their background.

We train year-round to continue expanding our skills, but most of us are unpaid volunteers, many with full-time jobs or other responsibilities, so we focus on learning the skills for just one or two roles. Training as an animal disaster responder has given me the opportunity to acquire all kinds of interesting skills, like ham radio operations, fireline safety, animal triage and first aid, and safe handling of many animal species like cats, dogs, rabbits, horses, sheep, goats, pigs, alpacas, chickens, turkeys, and even emus.

A typical field team in a big incident might have just two people (since we often just don’t have enough people available to form larger teams). One is the trailer driver (trained in trailer safety and maneuvering), and the other handles the navigation, paperwork, and radio. Both people assess and handle the animals.

Safety Comes First

To make the game more exciting, we have some rather dramatic scenarios. But in real life, we are very careful not to make things worse by putting human volunteers at risk. For example, we don’t send volunteers into areas at immediate risk of burning or flooding, or into a half-collapsed building. We use PPE (Personal Protective Equipment) like helmets, work gloves, etc., and we keep tabs on our field teams by radio at all times. Some of the equipment in the game (like the Fire Protective Gear) serves important safety functions.

The box cover art posed some interesting challenges – we wanted to show a lot of action without making it look too scary or dangerous. Claudia Sonder, founder and president of Napa Community Animal Response Team, helped me to spec out the water rescue scene for the illustrator with the appropriate equipment and PPE. Note that all the rescuers are wearing helmets, and all the people on the river are wearing personal flotation devices. The original art had a couple of safety elements that you can’t see (we decided to zoom the scene in a little for the final version) – the rescuer in the water is attached by a rope to the boat, and there are crates that the animals are being loaded into – that’s much safer than letting the dogs and cats just run around loose. That tired horse in the background is getting a forward assist to climb up the hill via a rescue strap around his chest – much better for him than pulling on his head and neck.

Different Types of Disasters Don’t All Happen at the Same Time

The game is designed to give a glimpse of lots of different types of disasters – fires, floods, mudslides, earthquakes, tornadoes, collapsed buildings, hazardous material events, contagious animal diseases, and even human-caused disasters like neglect and abuse cases. Individual animals also might need the help of a technical rescue team when they fall into a hard-to-access space or get stuck somewhere and their humans can’t get them out. (Real animal technical rescue teams even have the rigging equipment needed to airlift a horse with a helicopter.)

In the real world, you don’t get all of the disaster types at once like in the game. So, one incident might be a large wildfire with many homes burned, another might be flooding affecting livestock, and another might be a neglect case involving a bunch of small dogs. We would then choose volunteers for that incident who have the appropriate skills and equipment for the conditions (species-specific handling skills, animal first aid skills, trailer driving, technical rescue, etc.)

However, quite often one disaster will lead to another – for example, earthquakes can cause fires, collapses, and hazardous materials spills – so real life teams get exposed to a wide variety of challenges. A sudden evacuation might result in the discovery by first responders of previously unknown neglected animals who need care. Surprises happen all the time – you go to a property to pick up a couple of cats, but you drive by an injured goat on the way and end up loading her into the back of the SUV because you don’t have a trailer. I was once en route to a property to feed some donkeys when we were stopped by a first responder to warn us about a bear with burned paws who had been seen limping around nearby. Never a dull moment! But all of that said, the game definitely puts a lot more disaster scenarios side by side than we typically see in real incidents.

Sometimes There Are LOTS of Animals

A large incident like a wildfire can impact thousands of animals. The board game simplifies this to just a few animals per rescue so that the mechanics of the game are reasonable, but in the real world we might get a call to evacuate 30 horses from a boarding facility, or to provide food, water, and medical care for a flock 60 chickens or a herd of 25 goats. In the game, we used the mission cards to bring in some examples of larger rescues.

A lot of the challenge in a large animal response is in the paperwork – keeping track of who each animal is and exactly where they are at all times so that we can successfully reunite them when the time comes. We have to be careful when two similar-looking black horses come in at the same time to make sure we ID them correctly. But paperwork doesn't make for the most compelling game experience, so we only added it via the event cards "Paperwork Errors" and "Bureaucracy." Fun times!

Lisa comforting a dog who survived a large wildfire (photo courtesy of North Valley Animal Disaster Group)

Sometimes It’s Really, Really Sad

We wanted to keep the game hopeful and focused on the rescues, but field work can be pretty rough in a big wildfire. Sometimes we arrive at a property to search for an animal and all that’s left is a smoking ruin. I’ve had to make phone calls to tell someone that we couldn’t find their animal and they probably did not survive. Those phone calls wreck me every single time.

But sometimes it goes the right way. Someone has lost their home and all their possessions, but we get to call and tell them that, against all odds, we found their beloved cat and are headed their way to reunite them. It’s those moments that keep me going.

Creative Problem-Solving is Always Required

Some elements of the game surprised me with how much they feel like real world disaster work. The element of creative problem-solving is present in both. Real field teams are constantly asking: What do we do first? How much time do we have before things get dangerous? A fallen tree is blocking the road – can we remove it with the tools we have in the truck? Or instead, can we safely walk the last half mile to the property and lead the horses out? These pigs won’t load into the trailer; can we improvise a loading chute out of the materials lying around here?

Animals get up to all kinds of crazy stuff – some real-life stories that I’ve heard didn’t make it into the game because they actually seemed too outlandish. One recent example: some colleagues of mine were called to assist with extracting a pregnant cow from a swimming pool (I'm so curious how she managed to fall in there!). One possible method would involve passing some lifting straps under the cow’s body and hauling her out over the side of the pool, but this was ruled out because of the risk of injury to her unborn calf from the straps. The team ended up draining some water from the pool so that the cow could stand instead of swimming, and then they built a ramp to enable her to walk out on her own. A panicked cow is no joke to deal with, and a cow is less likely than a horse to be used to halters and human handling, so this rescue involved a lot of planning, creativity, and teamwork to come up with an effective method that kept everyone safe.

How Realistic is the Game?

I’ve been asked how realistic the rescue stories in the game are. Many of the scenarios on the rescue and mission cards were inspired by real-life rescues, but with details adjusted to keep things interesting and to suit the game’s mechanisms. In case you’re wondering, the rescue where the horse falls through the top of the septic tank is actually very realistic – we are trained to watch out for this hazard. A large fire can weaken the top of the underground tank, and when the horse (or a person) walks over it later they can fall through. The horse would definitely need some decontamination afterwards.

Regarding the game’s vehicles, real life field teams do use pickup trucks, SUVs, and trailers. Boats are heavily used in water rescues, but you wouldn’t likely see a boat being towed around during a wildfire incident. A car might be used in an incident that affects mainly smaller animals (but is less useful than a larger vehicle). The motorcycle is not that realistic for animal response simply because it can’t hold much in the way of equipment or animal carriers (although perhaps it could be used for scouting an area with poor road access). But for the game, the motorcycle is very fun – I love the visual of a chicken riding on the back!

Your Turn!

Despite the simplifications and adjustments we had to make, I think we've been able to achieve a lot of the feel of real world animal disaster response with the game. (One of my colleagues is actually toying with the idea of using the game as a training tool for new field team members.) It's been amazing to watch people playtesting the game, getting deeply invested in their complex plans to rescue the cats, while assembling specialists to save the horse, and wait, we need to drop off some equipment to help nail that mission, and OMG WHERE DID THIS TIGER COME FROM? AND WE'RE RUNNING OUT OF TIME ON THE DOG! AND NOW THE BRIDGE IS OUT, YIKES! That's exactly how it feels in the real world – we get tired and hungry, and things go wrong unexpectedly, but we keep going as long as we can for one more animal. And now, you can try this out for yourself!

Bonus Materials

Be sure to check out Lisa’s Real Life Animal Rescue Stories which also includes some stories where the animals are the heroes.

Here are some Tips for Being a Real Life Animal Rescuer. We also put these in our rulebook.

Notes

Fintan Leacock

Our family adopted Fintan in 2015. I never thought I’d want a dog, but Anna slowly worked on us by showing us detailed slide presentations, researching non-allegetic dog breeds, and agreeing not to complain about anything for 30 days. (That was some especially creative parenting on our part at the time.) Anna recalls that not complaining for that month was one of the hardest things she’s ever done in her life.

Players flew helicopters around and rescued animals from danger. Anna confirmed recently that she did indeed (despite earlier protestations) deliberately change the rules of the game during play so she would win every time.

Lisa added the tiger to the game based on real world stories of tigers and other wild animals being rescued from poor conditions under private ownership. This was long before the 2020 lockdown and the popular series, Tiger King.

Since the “2” result is on each die twice, you’re more likely to get the average total result of 4 (22.2%) than you are of getting a total result of 5 in Thunderbirds (16.7%).

I prototyped these using a laser cut illustration board. When illustration is cut in layers, stacked, glued, and painted, it’s a convincing proxy for wood. The motorcycle in this photo is also prototyped using illustration board.